MacroView in a nutshell:

- The scenario outlined in our last MacroView has not changed. We still expect higher interest rates and persistent inflation in the mid-term. It has been more than 12 months since economists and markets have been expecting a global recession, but growth remains somewhat resilient (except in China).

- There seems to be a dissonance between what is expected from the economy (recession) and what the economy is going through. Positioning on the belief that a recession will not appear and inflation will fall could be risky, just like positioning under the ‘transitory inflation’ assumption was risky in 2021-2022.

- We argue that the lack of a recession in the US after the aggressive tightening by the Federal Reserve is a sign that today’s levels of interest rates are not restrictive enough. We strongly believe that the real neutral rate of interest has risen since the pandemic and we might be, as we proposed last year, under a structurally different economy.

- If we don’t see a recession, inflation is set to remain high and continue to be the main concern for central bankers and markets. We expect inflation to remain high, especially in its core components. The longer inflation takes to come down, the higher rates will need to be, especially if the real neutral interest rate has risen, as we believe.

- The recovery in China has not been as strong as we expected, and inflation remains low. If things in China are worse than we think, if growth and demand doesn’t pick up towards 2024, then a scenario of global deflation is worth taking into consideration.

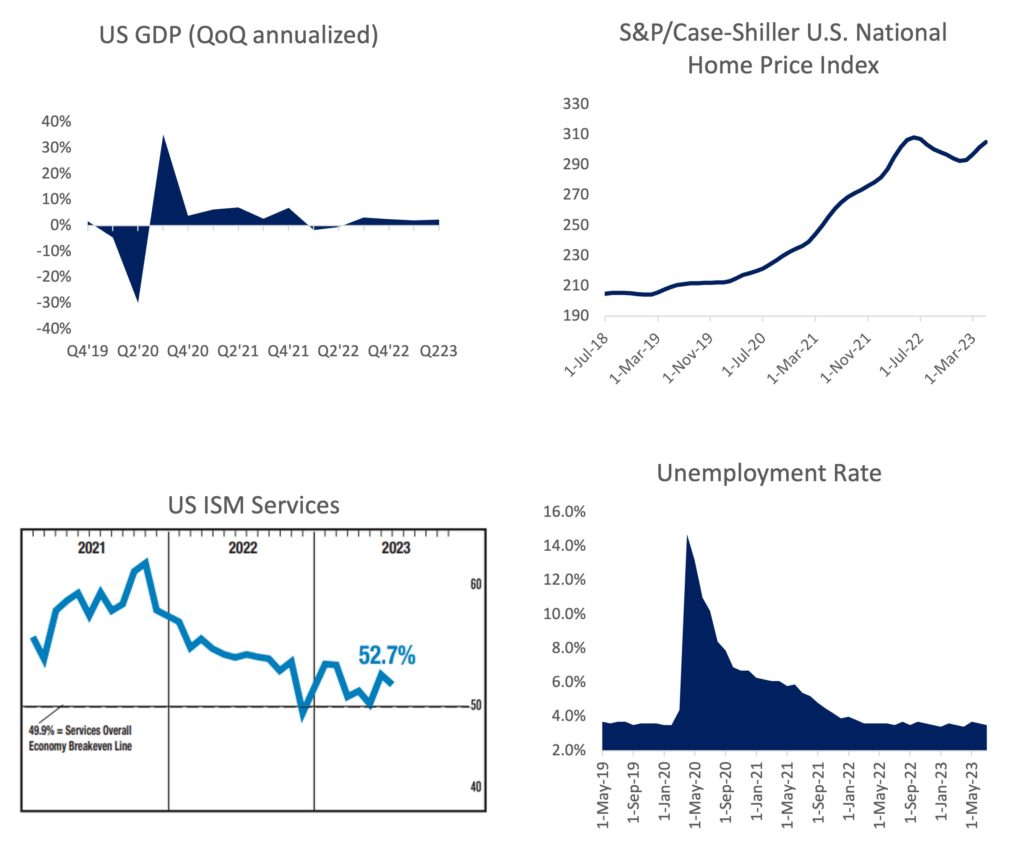

It has been more than 12 months since economists and markets have been expecting a global recession, given the aggressive monetary tightening by central banks during the past year. However, growth remains somewhat resilient, except in China. The world economic slowdown is more evident in the manufacturing sector, and we are still far from a generalized, deep, or protracted recession. In the largest economy (the US), growth accelerated in the second quarter of the year thanks to strong consumption, the housing market is showing signs of stabilizing, unemployment remains low and the services sector is still expanding (Figure 1). Thus, there seems to be a dissonance between what the economy should be going through –according to economic theory—, versus what the economy is going through.

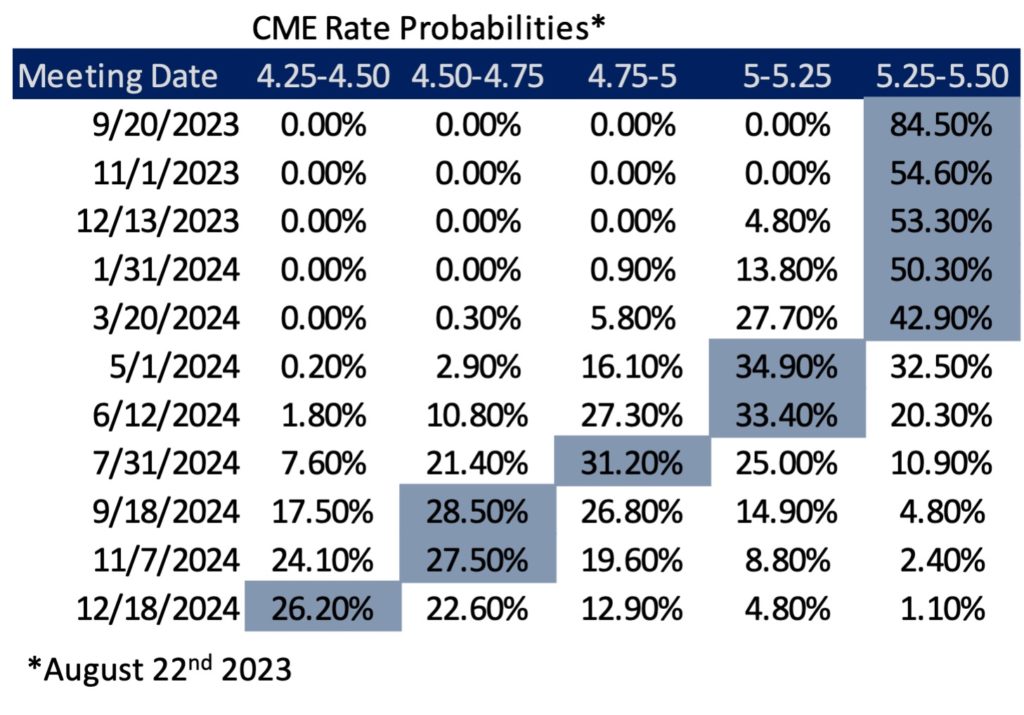

One way market participants have reconciled this dissonance between theory and facts is through the belief that a recession is just around the corner. A recession might not have manifested yet, but it is just a matter of time given the stringent monetary policy. This view was adopted by the consensus during the first half of the year, and it assumed that the economic resilience seen so far is just transitory, that growth will eventually wane and give place to a recession. Markets aligned to this expectation and had been pricing a recession in late 2023, or early 2024 . This view is still somehow dominant in the futures market, with rate cuts still expected by market participants in 2024. But not in equity markets, where growth resilience has propelled risk taking under the belief that a recession could be avoided. However, market sentiment has been shifting since late July. Markets are pricing the end of rate hikes by September, suggesting we are nearing a peak in monetary policy rates (Figure 2). At the same time, the probability of recession is being revised to the downside

Figure 1 - US economy overview

Figure 2 - CME Rate Probabilities

The longer the recession scenario takes to materialize, the more confidence among market participants on the possibility of avoiding a recession. In the last couple of months, given the positive inflation data and resilient growth numbers, bond and equity markets seem to be supporting with more confidence the possibility of an economic ‘soft landing’, a no-recession scenario despite the aggressive monetary policy by central banks. In our view, ‘no-landing’ or ‘soft-landing’ scenarios imply a trend of persistent higher inflation and will require more action by central banks, which would eventually take us back to the discussion of a recession. In this sense, a ‘soft-landing’ would be transitory, unless central banks admit higher inflation targets (above 2%) in the long term. However, markets seem to be gaining confidence on a soft-landing and falling inflation; a contradiction in our view: a mirage.

Positioning on the belief that a recession will not appear and inflation will fall could be risky, just like positioning under the ‘transitory inflation’ assumption was risky in 2021-2022. To give context: In the second half of 2021 and into 2022, the market consensus considered that the inflation problem arising from the pandemic recovery was a ‘transitory’ phenomenon. The idea was that inflation would fade fast, as the economy returned to its normal functioning and the supply shocks of the pandemic disappeared. The Fed coined the term ‘transitory inflation’ and decided to delay the end of monetary stimulus until March 2022, when they realized inflation wasn’t ‘transitory’ as thought. Of course, at that time the Ukraine war and the subsequent shock in energy and agricultural commodity prices was an important catalyst for the dramatic change in inflation expectations by the Fed and market agents. But it was the complacency that did most damage to market participants: a blind belief that inflation was ‘transitory’, that interest rates would remain permanently low and that things would not change after the pandemic. That embedded belief caught most market participants off guard and represented important wealth losses for portfolios positioned in long duration assets.

So, if we take past events as a guide, under the current circumstances it could be smarter to consider the possibility of the market consensus being wrong again, or perhaps just too optimistic. Maybe we have not reached the peak of interest rates, and, sooner or later, we won’t be able to avoid a recession. It seems ‘healthy’ to step back and consider views other than the ‘soft-landing’ posture. We propose another way to reconcile theory with facts in today’s environment, one that differs from the market consensus. It is possible to argue that the lack of a recession in the US after the aggressive tightening by the Federal Reserve is a sign that maybe today’s levels of interest rates are not restrictive enough. Maybe interest rates still have some way to go before aggregate demand and inflation experience a more sensible impact from monetary policy. Maybe there has been a major structural change in economic dynamics that requires a revamp of our assumptions on how the economy works.

Let us be clear. A recession is still the most probable outcome in our view, but perhaps it won’t come to materialize with a 5.5% handle in US policy rates. We might have to see first higher interest rates, between 6%-7%, according to our calculations (see MacroView March 2023). Even after the crisis in regional banking and a decline of credit availability, financial conditions have continued to ease, and the US economy remains robust. Growth is at most starting to signal a mild recession or a cyclical, temporary downturn. As we outlined in our previous MacroView, we do not believe a moderate or cyclical downturn in growth will be enough to lower inflation pressures. We remain in the position that the Fed will have to keep rising rates to achieve its goals and that the biggest risk we face right now is that they claim victory over inflation too early. However, further action by the Fed in the coming months also risks financial instability and a recession. As we put it in past MacroView editions, the central bank’s position is tough, they must choose between two bad outcomes: recession or higher inflation. We believe the Fed still prefers a recession over hot inflation, but they are being cautious lately with their actions because the monetary tightening has already been very aggressive. However, there are no clear signs of waning aggregate demand, and that creates uncertainty. Why hasn’t there been a recession or a more pronounced economic slowdown if interest rates are at their highest level in 22 years?

We strongly believe that the real neutral rate of interest, something known as R-star in Economics, has risen since the pandemic. And that is what’s causing a dissonance between what is expected from the economy (a recession) and what is happening (resilience of growth). R-star is the real neutral rate of interest or “equilibrium rate”. It is a rate of interest that is neither expansionary nor contractionary when the economy is at full employment. It equilibrates the economy in the long run: it provides enough incentives for credit to grow, so that investment and spending grow too; but it keeps price increases and inflation in a moderate path of expansion.

The most important idea to grasp from R-star is the following: if the central bank sets the policy rate below R-star, the monetary stance is accommodative and favours inflation; on the contrary, if it is above R-star, it is restrictive and should help cool the economy. Thus, R-star is essential for the formulation of monetary policy and is the key factor to understand today’s events.

The NY Fed has estimated R-star somewhere around 0%-1%, even after the dramatic economic shifts caused by the pandemic. This is crucial, because this means that the NY Fed, pretty much like the markets, seems to be backing the idea that low interest rates are here to stay and that the recent bout of inflation and higher interest rates is not to last for long. According to this view, the high inflation and interest rates environment it is an exceptional state of the economy that will correct and give place to what we were used to in the pre-pandemic era: low interest rates, low inflation, and moderate growth. The key assumption here, and something that we believe is fundamentally wrong, is that the economy has suffered no relevant changes since the pandemic, that the global economy is essentially the same as before 2020 and we are just on our way back to ‘normal’. If we assume the NY Fed is right when they estimate R-star at a 0%-1% real rate, then today’s policy stance is already restrictive.

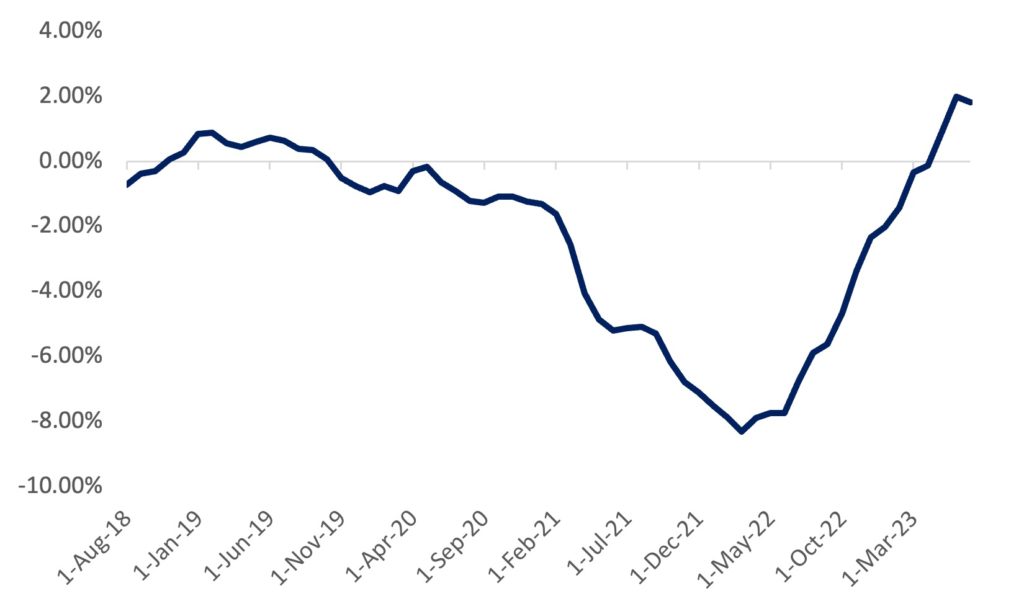

Figure 3 - US Real Rate (short term ex-post)

But this is not consistent with what is shown in data. If R-star remains as low as in the pre-pandemic era, the aggressive increase of interest rates of the past year should be enough to provoke a recession and there are no signs of a recession yet. It could be that some other factors should be considered when measuring R-star, as pointed out by researchers at Citadel: the soundness of private-sector balance sheets, steady fiscal support from industrial and security policies could be supporting the economy in a high interest rate environment. Thus, a restrictive policy rate could not be causing the damage expected in the economy. Or perhaps we should believe Edward Price when he writes that R-star is non-existent, a theoretically built concept that says nothing about real matters. Whatever the position, estimating R-star between 0%-1% is not consistent with empirical evidence.

The lack of consistency between data and the estimation of a low R-star leads us to believe that, even if we do not fully understand the changes brought by the pandemic (remote work, new spending habits and preferences, geopolitical fragmentation, nearshoring, etc.), it could be wiser to assume they are fundamentally changing how the global economy works. So, we assume the opposite, that the US and the global economy has in fact experienced change, and it is no longer going back to the same state it was before COVID. Spending and saving decisions have changed, and most importantly, the real neutral interest rate (R-star) has risen since the pandemic.

Even with interest rates at their highest in 22 years, it is possible that the neutral interest rate has not been reached. R-star could be higher than in the pre-pandemic era. What could cause its rise? R-star fundamentally depends on economic agent’s preference to either save or invest. When agents prefer to save, R-star lowers; when agents prefer to spend or invest, R-star rises. Also, it is thought that above trend growth contributes to a higher R-star. Has the pandemic put in place dynamics that are strong enough to make a sensible change in a structural, slow-moving variable like R-star? Or are there other factors at play? Answering these questions could take us years. Because R-star is structural and slow moving, it is dangerous to use cyclical indicators to justify its rise. Real rates (short rates less headline inflation) tend to mean revert, but over decades, not years. Moreover, there is little empirical evidence of a direct link between growth and R-star changes. Thus, understanding this shift is a real challenge that surpasses the objective of this MacroView.

But in a practical sense, we prefer to assume that we are entering into a higher rate environment, a new ‘equilibrium’, a new regime, different from that of the pre-pandemic era. That is all we can conclude from the fact that actual interest rate levels (in real terms) are not causing an evident recession globally. We might be, as we proposed last year, under a structurally different economy.

If we don’t see a recession, inflation is set to remain high and continue to be the main concern for central bankers and markets. We expect inflation to remain high, especially in its core components. Although the recent rise in salaries is not particularly worrying, it remains constant, and that suggests a deeper inflationary problem ahead. Without a significant economic slowdown that guarantees a return of inflation to its pre-pandemic levels in the short or medium term, high core inflation could push the Fed to hike rates up to 6-7% (see MacroView March 2023). The coming months, especially those towards the end of the year, are crucial for confirmation of this scenario.

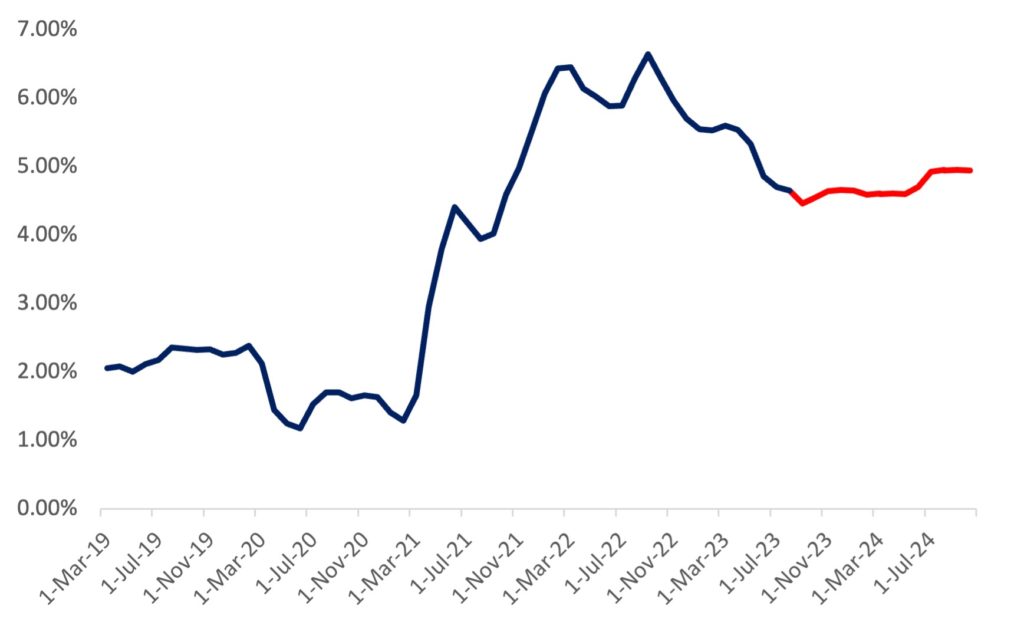

Headline inflation in the US has come down near 3% annual rate during June, but it is expected to rebound in the coming 3 months as base effects dissipate. From there, if energy prices continue subdued, inflation could slowly come down again to 3% and reach 2.5% at the beginning of 2024. However, once those levels are reached, it is expected to stabilize and, if core inflation remains high, it could start to rise again during 2024 to reach 3% towards November. This means headline inflation could stabilize around 2.5%-3%, with risks of rising slowly if core inflation remains high. Our models show that Core could stabilize around 4.7%-4.9% in the second half of 2024, which is quite high and unacceptable for the Fed. To put it into perspective, Core inflation was at 4.85% in June and 4.7% In July and, if our models are right, we might not see much lower levels from here on. Only a recession and an important slowdown of aggregate demand would help Core inflation inch lower, but that would need more actions from the Fed to tighten monetary policy. That is why we see the Fed continuing to raise rates during 2023, until the trajectory of Core inflation is lowered.

Every data point in the coming months will be key to understand if the evolution of inflation is favorable for a pause in rate hikes or not, but if core inflation keeps its actual trend, no rate cuts or prolonged pause in rate hikes should be expected.

Figure 4 - US Core CPI with Forecast

Inflation numbers have been better than we initially thought during 2023 and that is a good sign. But markets are too optimistic if they think today’s monetary stance is enough to see inflation come lower in the short and mid-term. Energy prices have been at the forefront of lower Headline inflation for the past few months, plus some base effects. We think there is a high probability of a rebound in energy prices, as oil futures prices have seen a rally of around 21% since early july. Food prices also remain high, and they could keep feeding inflation pressures more broadly.

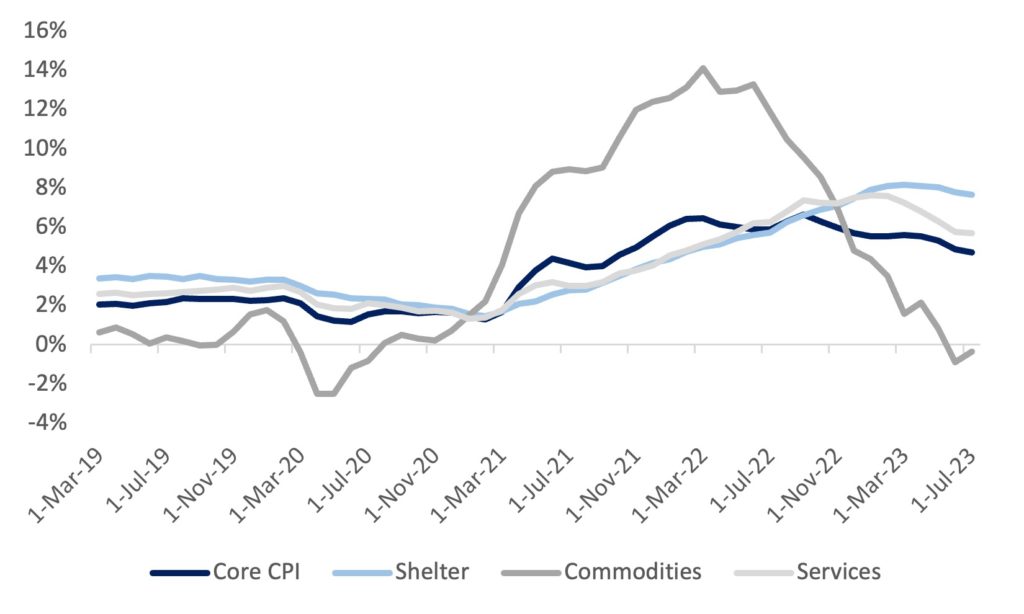

In Core inflation, transportation and medical services’ prices have come down more than we initially thought, but shelter and housing costs remain stubbornly high. Being shelter the most important component of Core inflation, it is important to see a moderation of these prices towards the end of the year; otherwise, Core inflation will remain high. Recent data has pointed to a resurgence of demand in the housing sector, so a moderation in these prices is not our base case. We need to see data of a cooling housing market and a rising unemployment rate to believe core inflation will moderate.

Figure 5 - Core CPI and components

With inflation still high, the Fed has remained hawkish in the most recent FOMC meetings, and markets have had to gradually remove any expectation or rate cuts in 2023. Nonetheless, they still expect cuts in 2024. Market expectations of rate cuts in 2024 has been supported by the FOMC, who has also penciled rate cuts by 2024 in their latest macroeconomic projections, based on the assumption that inflation would fall and, despite lowering nominal rates, real rates would remain restrictive. But if no recession takes place and inflation rebounds in 2024, that lower path in interest rates will be hard to put into practice. Have no doubt, if there is no improvement in core inflation, markets could end up taking back the expectation of rate cuts in 2024 altogether.

The longer inflation takes to come down, the higher rates will need to be, especially if the real neutral interest rate has risen, as we believe. We estimate R-star at 2% (real rate), double what the NY Fed has estimated. But the actual level is highly uncertain and central banks are operating almost blind, without certainty about where the appropriate level of restrictive policy is. Thus, if inflation proves to be stubborn and rates continue to creep up, the higher the risk of a recession or a financial accident. The landscape has not changed much in the last 6 months, and it doesn’t seem to be different for the rest of 2023 and 2024: markets will continue to fluctuate between the risks of higher inflation and the risks of a recession. At the moment, we are in an episode of optimism that could fade quickly.x|

On the other side of the world, things couldn’t be more different. The recovery in China has not been as strong as we expected, and inflation remains low. Although lockdowns have disappeared and oil consumption in China has reached a new record high in April, general spending in the domestic market has remained subdued. Retail sales, a good proxy for spending, grew at its slowest pace since last December (3.1% YoY, July). The rebound seen in April is fading quickly. The service sector is also expanding at a more moderate pace according to the PMIs and youth unemployment reached a new record high of 21.3% in June. Chinese exports saw their biggest drop in 3 years during July (-14.5% YoY) and imports also saw a deep contraction (-12.4%). All bad news for an economy that 3 months ago was expected to recover. The effects of the housing market crisis seem to be more profound than thought, especially for consumer confidence. There are no signs of a strong rebound in economic activity and authorities have not pulled the trigger on any aggressive stimulus measure. That is increasingly making us question our thesis of a strong China recovery. Authorities have committed to avoiding any regulatory change that could threaten the growth of key sectors and have reaffirmed their willingness to support economic activity. But they have stopped short of announcing any major action and have preferred more nuanced and focused support, something that has kept markets skeptic about the ability of China to recover fast. If there is no strong recovery in China, global growth could remain subdued.

For how long could Chinese underperformance continue? That is the second most important question to answer to understand the global growth and inflation environment. Inflation in China has surprised to the downside, with inflation flat in June and leaning towards deflation in July (-0.3% YoY). If things in China are worse than we think, if growth and demand doesn’t pick up towards 2024, then a scenario of global deflation is worth taking into consideration. This is the strongest argument against our view of higher inflation for longer. If China is in a worse position than we assumed, if the crisis has not reached its bottom and growth keeps disappointing, some deflationary pressures could already be at play. Thus, contemplating alternate scenarios to our base case is of crucial importance.

Alternative Scenarios

Our base case is high inflation that pushes for higher rates in the medium term and eventually a recession. The scenario of a “soft-landing” seems to be gathering more traction, but if it materializes it will only be an intermediate situation before a recession; and it will call for higher rates, anyway. There is a higher probability of this happening than it was a few months ago, but in the end, the scenario is not much different from our base case: higher rates will ensue sooner or later, with risks of persistent inflation and unhinging inflation expectations. There are two alternate scenarios that need to be considered:

- The FED blinks – The Fed could stop hiking rates in late-2023, either because a more pronounced deceleration of growth takes place, because they claim victory over inflation early or because of continued financial instability. Whichever the case, this poses a high risk for more entrenched inflation and the unhinging of inflation expectations. This could prove costly. As we outlined in previous reports, this could prompt a scenario where the Fed would have to restart rate hikes sooner than later (a “stop-and-go scenario”) and reinforce stagflation.

- Inflation comes down – Although inflation pressures remain strong, a scenario where inflation comes down fast is not out of the cards. We think this would have to come in the form of a deep and protracted recession that wipes out any inflationary and salary pressures. So far, in the US there are no signs of such a deep recession (dares us say depression), but in China things could be much worse than thought and that could be the force behind subdued commodities demand and low inflation. In a fast-evolving environment, conditions must be constantly evaluated. A deep recession is still a distinct possibility, given the steep increase of interest rates and the high levels of debt around the world; plus, the housing crisis in China could be deeper than admitted by the Chinese authorities.

Investment opportunities

We recommend keeping an eye on a few dynamics when making investment decisions. Credit market spreads in the US will be a great barometer to measure financial conditions and recession risks. Also, keep an eye on the Bank of Japan. We believe that when the BoJ abandons Yield Curve Control or allows a wider fluctuation of 10-year JGBs, US and European credit markets might suffer a drainage of liquidity, as Japanese pension funds repatriate capital. Also, don’t lose sight of inflation and its dynamics; salaries will become more and more important if we don’t get a deep recession. And, finally, monitor inflation expectations through US Treasuries’ break-evens. The anchoring of inflation expectations or its unhinging is key to understanding what might come next.

Long Gold and Silver — We believe precious metals have already started its rally to new highs in the medium and long term. They still present attractive risk-reward ratios and it is still a good time to build positions in these assets. Platinum is also an attractive asset to play the same idea. We see a strong potential for precious metals in all the probable scenarios described above: a long-lasting inflationary environment with risks of unhinging inflationary expectations; low growth; or in a scenario where the Fed stops rising rates and real rates compress.

Credit spreads widening — Credit market spreads in the US will be a great barometer to measure financial conditions and recession risks. As markets digest a higher rates and inflation environment, yields for US treasuries could creep higher and lower rating instruments could see yields rise more violently. Also, due to the pace of rate hikes and inflationary forces that erode margins and growth, we expect a violent move in the next quarters on credit spreads. We are now on a different playfield in terms of the cost of financing, and debt levels are high enough to lead to some corporate and maybe sovereign debt bonds imploding.

Long Chinese equities — After an initial rebound in Chinese equities at the end of 2022, prices have come back down in this space. It remains a good moment to build positions in Chinese equities. The risk-reward is very attractive and, given that an initial rally has already taken place, the trade can be carried with much less risk. However, it is important to be alert, as the macro background has not improved substantially and it is key to eliminate exposure if there is no better performance in Chinese assets by early 2024.

Defensive stocks — We favor stocks of businesses that have a strong cash flow generation, a ‘floor’ in the demand for the products they produce (demand inelasticity) and a healthy balance sheet. There are good dividend yields in the consumer staples and energy sectors.

Long commodities — This asset class has been very sensible to recession fears and its volatility has pushed us to reduce exposure. Although, in the mid to long term we believe it is a great asset to have. We’ve continued to cut some exposure to agricultural commodities in the last few months and realized some losses, as prices of the asset class have continued to adjust down under fears of recession. However, we are still holding Wheat and Coffee positions. For Oil, the outlook remains uncertain, and it is important not to rule out the possibility of seeing international prices reaching $50dpb (WTI) levels towards the end of the year. A rally to $90 could still happen before that correction, but we do not believe it is worth the risk. We have completely liquidated our position in Oil. For Copper, we are taking exposure in search of a rebound to the highs seen in early 2022 and late 2021, and in Natural Gas we have started to build a position with the winter in sight.

Short US Bonds — We still favour a scenario with a higher rate environment and a probable unhinging of inflation expectations. Our exposure is moderate-low, as it is still possible yields will head lower (and bonds’ prices higher) in a recessionary environment. With the US10y yield as a reference, we expect it to break 4.5% before year end before we can position more confidently. If a break fails to materialize, yields could come down to 3%-2.5% before we can add more to our long-term strategic position of net short US bonds.

Long USD — Taking the DXY Index as reference, the dollar tested levels near 99 and has since shown signs of a rebound. If a Fed pivot takes place, the Dollar might lose ground, so it is prudent to not assume much risk in this position. But in general, we still favour the dollar and dollar denominated assets, like T-bills and short-term debt.

Disclaimer

This report contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of the federal securities laws. Forward-looking statements are those that predict or describe future events or trends and that do not relate solely to historical matters. For example, forward-looking statements may predict future economic performance, describe plans and objectives of management for future operations and make projections of revenue, investment returns or other financial items. A prospective investor can generally identify forward-looking statements as statements containing the words “will,” “believe,” “expect,” “anticipate,” “intend,” “contemplate,” “estimate,” “assume” or other similar expressions. Such forward-looking statements are inherently uncertain, because the matters they describe are subject to known (and unknown) risks, uncertainties, and other unpredictable factors, many of which are beyond FESC Asset Management, LLC control. Actual results could and likely will differ, sometimes materially, from those projected or anticipated. We are not undertaking any obligation to update or revise any forward-looking statements whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise. You should not take any statements regarding past trends as a representation those trends or activities will continue in the future. Accordingly, you should not put undue reliance on these statements.

Actual results may vary substantially from past performance or current expectations. FESC makes no guarantees and no representations whatsoever related to any forward-looking statements or future results or events. The information contained herein is believed to be accurate as of the date of preparation, and FESC reserves the right to change and/or update such information at its sole discretion without prior notice. Investments are subject to market risk, including the complete loss of principal. Asset classes or investment strategies described may not be suitable for all investors. Equities and all other asset classes discussed herein are subject to market risk meaning that stock or asset prices, in general, may decline over short or extended periods of time.

The information contained does not consider any investor’s investment objectives, particular needs, or financial situation. Nothing in this material constitutes investment, legal, accounting, tax advice, or a representation that any investment or strategy is suitable or appropriate. FESC and its personnel gathered this information from publicly available sources, and we do not guarantee its accuracy.

The information herein is only a summary and does not purport to be complete. The information contained herein has been prepared by FESC solely for informational and discussion purposes only and is not for public distribution. This report does not constitute an advertisement, an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities or investment advisory services and is intended for informational purposes only. This presentation is strictly confidential and may contain private, proprietary, secret, and commercially sensitive information and may not be reproduced in any way or form or disclosed to any other person without the previous written consent of FESC.

Investment advisory clients, employees, and employee-related accounts may engage in securities transactions inconsistent with this report.

The above information is subject to change without notice. Additional information is available upon request.